- Home

- Pavel Mandys

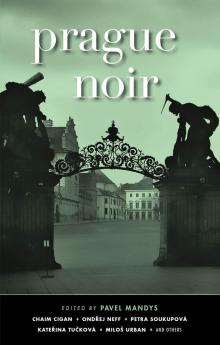

Prague Noir

Prague Noir Read online

Table of Contents

___________________

Introduction

Sharp Lads

Three Musketeers

Martin Goffa

Vyšehrad

Amateurs

Štěpán Kopřiva

Hostivař

Disappearances on the Bridge

Miloš Urban

Charles Bridge

The Dead Girl from a Haunted House

Jiří W. Procházka

Exhibition Grounds

PART II: Magical Prague

The Magical Amulet

Chaim Cigan

Pankrác

Marl Circle

Ondřej Neff

Malá Strana

The Cabinet of Seven Pierced Books

Petr Stančík

Josefov

PART III: Shadows of the Past

The Life and Work of Baroness Mautnic

Kateřina Tučková

New Town

All the Old Disguises

Markéta Pilátová

Grébovka

Percy Thrillington

Michal Sýkora

Pohořelec

PART IV: In Jeopardy

Better Life

Michaela Klevisová

Žižkov

Another Worst Day

Petra Soukupová

Letná

Olda No. 3

Irena Hejdová

Olšany Cemetery

Epiphany, or Whatever You Wish

Petr Šabach

Bubeneč

About the Contributors

Bonus Materials

Excerpt from USA NOIR edited by Johnny Temple

Also in Akashic Noir Series

Akashic Noir Series Awards & Recognition

About Akashic Books

Copyrights & Credits

Introduction

Noir? In Prague?

How do you write noir in a city where, until 1990, the profession of private detective didn’t even exist? Where the censors cultivated a positive image of the police in both media and literature? Where, in essence, organized crime was nowhere to be found, and the largest criminal group was the secret police? Before you delve in and start reading the fourteen stories in this collection, a heads-up: most of the stories are linked to Prague more closely than the noir genre, especially if “noir” is interpreted, narrowly, as a subgenre of the mystery genre. If, however, the concept of noir is extended and considered a label for literary works that contain elements of crime, danger, and menace, or where main characters find themselves in a critical situation, then you will find fourteen such stories in this collection.

The history of the Czech literary detective story is not very diverse, and the subgenre known as noir appears in it only sporadically. The main reason for this is the forty-year existence of a police state which carefully ensured that the propagandistic image of its repressive elements wasn’t questioned in the arts, including literature. And it is precisely noir stories that oftentimes do without the police; if they do appear, it’s usually in a secondary (and not always flattering) role.

At the center of noir literature is a solitary hero who must stand up on his or her own to either the crime or to some inner demons. That is a situation unfit for an exemplary member of a Socialist society. It was unseemly and undignified, and as such, official publishers were not allowed to publish many of these narratives. At most they could publish stories set in the corrupt capitalist foreign world and—according to the ideologues—they were supposed to demonstrate to their enthusiastic Czech readers how dangerous and ugly life behind the Iron Curtain was. Czech detective stories in those days were formally modeled after the traditional British whodunit: an even-tempered investigation carried out by a sympathetic policeman. After all, there was no such thing as a private detective in the Socialist regime.

It wasn’t until after the Velvet Revolution in 1989 that private detectives appeared in Czech novels. Nevertheless, it was obvious that most of them were based on foreign examples—there was still an inclination to use the classic British model. When Czech authors finally began to write stories in the tradition of the hard-boiled American style, it did result in more naturalistic and action-driven novels. The basic theme of the detective who solves crimes, however, remained unchanged.

But noir in its best form—even if the term itself is still somewhat unclear and used with many meanings and contexts—does not really follow this template. The point is not that the mystery of a cunning murder is always successfully solved by a smart detective, but that the reality of men and women somehow ends up embroiled with crime, in the role of investigators, witnesses, victims, and perpetrators. The endings are not always happy; they do not even always offer a clearly solved case or apprehension of a murderer. On the contrary, the best noirs end tragically, or at least ambiguously. Disillusionment and disappointment are the basic emotions of most noir heroes.

The most popular Czech detective prose from past years uses the concept of friendly neighborliness—these are small stories of small people who sometimes do bad things. This is not surprising given the lack of organized crime in the Czech police state. Its chief representative was a secret faction called the State Security. Particularly the older generation of authors, who were publishing in the nineties and at the beginning of the twenty-first century, could not, or did not want to, break from this tradition.

A more marked change came with the popularity of Scandinavian crime novels, which have demonstrated that even in the countries with the highest quality of life and the lowest crime rate in the world, incredible stories can be developed about gruesome murders and their complex investigations with ambiguous conclusions. And the noir environment has been created there too: entrepreneurial elites and politicians in the Czech Republic interfaced very quickly with organized crime, and the police and justice systems were not pure either, as many scandals in the media documented.

Yet Czech authors do have an advantage: Prague’s history in the twentieth century is far more dramatic and colorful than the history of any American city. During the last century, Prague was part of several different states and nations, all of which varied both politically and geographically. First, until 1918, Prague was part of a multinational Habsburg monarchy which ceased to exist following World War I. In 1918, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk brought a vision of a democratic state of Czechs and Slovaks from America, and thus Czechoslovakia was formed—one of the very few democratic states in Europe at that time. But Nazi troops soon entered Prague, and the independent republic became the Czech and Moravian Protectorate.

The liberation by the Russian army brought only a short restoration of democracy. In 1948, Communists supported by Moscow seized power and established a new despotism which was only slightly milder than the Nazi regime, but which lasted much longer. The Czechoslovak Republic added the word Socialist to its name so that its membership in the Communist bloc was clear. The Soviet Union had no qualms about demanding this membership by force in 1968, when the Czech nation tried to break off from the totalitarian regime, and the Russians sent their army to Prague. The Czechs had to wait until 1989, for the fall of communism, to overthrow the regime in a peaceful, democratic way. But even that did not bring the end of the turmoil. In 1992, Slovakia broke off from the single Czechoslovak state, and Prague became the capital city of the Czech Republic.

These dramatic and turbulent historic changes have not just become items in history textbooks; they had real-life consequences for all the inhabitants of Prague. In 1938, it was still a very lively city, where Czechs, Germans, and Jews cohabitated. There was an influx of refugees from European countries where totalitarian regimes had come to power—specifically, from Communist Russia and Nazi Germany.

The Nazis then later almost totally wiped out the Jewish citizens. Conversely, in 1945, almost the entire German population was expelled from Prague. After 1948, all major private factories and companies were put under government control, and the smaller stores and shops soon followed. The state confiscated apartment houses and large villas; citizens could not own any sizable properties or businesses. Successful businessmen, large farmers, and even people who simply disagreed with the ideology of the regime ended up in prison if they hadn’t already saved themselves by escaping abroad, which was forbidden and punished. Everything was dictated by the Communist Party—which was, in turn, directed from Moscow. It wasn’t until the nineties that the victorious democratic movement led by Václav Havel tried to redress these historical injustices, and started to return property and a good reputation to all those who had been robbed by the Communist regime.

It is good to realize this context because many of the authors of the stories included in Prague Noir work within it. Historical twists and their intersection with the everyday lives of Prague’s inhabitants are a theme of the stories included in the section called “Shadows of the Past,” most notably in Kateřina Tučková’s story “The Life and Work of Baroness Mautnic,” and in Markéta Pilátová’s story “All the Old Disguises.” Chaim Cigan’s (alias Karol Sidon) piece “The Magical Amulet,” although I included it in the section “Magical Prague,” has similar themes. This section depicts another important feature of Prague, renowned for the many magical stories and macabre legends from its many historical periods. According to connoisseurs of folk tales, every one of Prague’s historical districts, which luckily experienced no destruction in any of the European wars, has a high concentration of ghosts and phantoms per square meter. That’s also a reason why this side of Prague can’t be omitted.

Unlike novels of social criticism or magical realism, Czech crime novels have so far been translated only very rarely (here one has to note an exception: Innocence; Or Murder on Steep Street by Heda Margolius Kovály). As I have already mentioned, the history of the Czech literary detective story has not been—thanks to the social and political circumstances of recent history—voluminous, and on the whole not of high quality, although one can find many pearls. Perhaps the most interesting (and darkest) in this regard is the work of Prague-based, German (mostly Jewish) writers Gustav Meyrink, Franz Werfel, and ultimately Franz Kafka (the novel The Trial does, after all, contain a criminal plot). But this type of Prague literature was erased in the year 1939, and there was nobody to continue the tradition.

This is why I decided to approach authors who do not solely write detective novels, but do use, more or less, the genre’s props and methods. The first is the maestro of Prague mysteries, Miloš Urban, who already has under his belt one purely noir novel (She Came from the Sea). Then we have Petr Stančík, who’s been very successful both here at home and abroad with his latest novel, A Mill for Mummies, a captivating, humorous antidetective story based in nineteenth-century Prague. Kateřina Tučková likes to use the investigative method in her best sellers; the stories in the triptych To Disappear by Petra Soukupová also have criminal motifs. The novel Tsunami Blues by Markéta Pilátová is a Czech woman’s variation of the excellent spy dramas by Graham Greene; Chief Rabbi Karol Sidon, under the alias Chaim Cigan, has started to publish a tetralogy, Where Foxes Bid Good Night, a thrilling story set at the end of the Communist regime, and infused with criminal and surreal elements in an alternative reality. Sci-fi stories by Ondřej Neff often contain noir plots, and the popular writer Petr Šabach likes to depict witty tales about outsmarting the criminal element.

Fortunately, in recent years there have emerged novels by new authors who have breathed fresh air into the genre, sometimes from unexpected places. University professor Michal Sýkora writes carefully constructed books inspired by current British police procedural novels; Štěpán Kopřiva has emerged with perhaps the best of the Czech hard-boiled school, Rapidfire; and Jiří W. Procházka, alongside his partner Klára Smolíková, has introduced a detective series with the novel Dead Predator. An erstwhile policeman writing under the pseudonym Martin Goffa has transferred his police experience into literary form with a few novels and a collection of stories. Michaela Klevisová has found her niche in psychological detective stories, where who was killed and how is not as important as the portraits of the characters and their conflicting ambitions and motivations. Even a respected author of children’s books, Iva Procházková, has written an excellent detective thriller.

Prague Noir is a colorful collection in which some of the stories are linked only loosely to the noir genre (“Epiphany” by Šabach, or “Olda No. 3” by Irena Hejdová, whose neighborly themes put her closer to more classical writers like Karel Čapek), while others are examples par excellence (particularly “Three Musketeers” by Goffa). “Amateurs” by Štěpán Kopřiva is of the hard-boiled school, while “Percy Thrillington” by Sýkora is a classic detective story. Some of the authors draw from their previous books: Petr Stančík revisits the hero from A Mill for Mummies, the unorthodox Commissioner Durman; Petra Soukupová varies the motif of a sudden and unexplained loss of a family member, which was typical in her stories from To Disappear; Kateřina Tučková examines the history of a woman marked by the wrongs of the Communist regime; and Markéta Pilátová’s “All the Old Disguises” recalls, again, the globetrotting stories of Anglo-Saxon authors.

Ondřej Neff offers a romanetto in the tradition of a classical writer of Prague horror, Jakub Arbes; Miloš Urban writes an over-the-top action story set on the Charles Bridge; Jiří Procházka ventures into the world of circus folk in an amusement park; Chaim Cigan looks into the past of a Jewish family; and Michaela Klevisová contributes a delicate story about the closeness of an unexpected and irrational danger.

I see Prague Noir as a chance for Czech authors to introduce themselves to international—especially Anglo-Saxon—audiences at a time when there are fewer and fewer translations into English being published. Czech literature of the twentieth century has quite a few world-renowned authors (Jaroslav Hašek, Bohumil Hrabal, Václav Havel, Milan Kundera, etc.). Our literature of the twenty-first century, however, barely touches this platform. One of the reasons must surely be that the fame that the Czechs gained from the Velvet Revolution has passed, and what’s left is Prague’s reputation as one of the biggest tourist magnets in the world. Contemporary Czech literature is vivid, vibrant, and informed by contemporary world literature which—thanks to active translators—is usually available in Czech very fast. It is global and local, poetic and humorous, filled with stories from the past, present, and from imaginary worlds. And it is waiting for when, in addition to all the enthusiastic Czech readers—according to global statistics, the Czechs, along with Canadians and Norwegians, are the most diligent readers—it will also gain a greater international audience.

Pavel Mandys

Prague, Czech Republic

November 2017

PART I

Sharp Lads

Three Musketeers

by Martin Goffa

Vyšehrad

It’s fall, the end of November—disgusting and bleak. Only a few moments ago it was still raining, and for most of the day, waves of fog swept through the city. In the place where I am waiting right now, however, this kind of weather seems fitting. Perhaps there is no sort of weather that would not suit this place. Hot weather is bearable here; snow comes across as majestic; cold and rain only emphasize its mystique, so that you can almost hear the clatter of horse’s hooves and the clash of swords and shields.

During the day you love this place, and at night you fear it. But it beguiles you just as light does for moths. Once it ensnares you, you will forever be coming back here. Just like me.

When I moved to the city twenty years ago, the small window in my kitchen offered a direct view of the castle walls. It was less then a day after that I was atop them, above all the surrounding roofs, walking along and watching th

e river and the blocks of houses below. A few years later, just a short distance from here, I was standing there with my bride right after the wedding ceremony, still in our wedding clothes. We felt not only as if Prague belonged to us, but the entire world, and all that was living, was ours too.

Well, here I am again, alone as I almost always am these days. That woman has been gone for a long time, and the child that I wanted to show all of this beauty to one day, she decided to have with somebody else. But none of that is Vyšehrad’s fault. It has witnessed millions of similar and worse fates.

My breath turns to mist. When I walk, the wet grass softens my steps. Below me I see strips of lights, but up here, by the castle walls, it’s dark. I took care of a few lamps last night, and just as I imagined, so far nobody has fixed them. The conversation which is going to take place here soon is best accompanied by darkness. I don’t even know what time it is—perhaps midnight—but time means nothing to me. Not now, for sure, and most decidedly not here. But it’s futile to try to explain. Those who know this place know what I mean; those who do not wouldn’t understand.

Twenty or thirty more minutes pass. Around me there’s only silence, while the city fusses with its ordinary life. I’m awaiting footsteps—the crunching on wet sidewalk gravel. Time passes, but I know that I will eventually hear it. I’m not afraid. I fear nothing. In fact, I feel strong; stronger then ever. As if those thousands of souls lying in the cemetery just a short distance behind me are protecting me.

I lift my hands and breathe into my palms. I could put my hands into my pockets, but I want them free, I feel better that way. I should have taken gloves, it occurs to me. Finally, I hear somebody approaching. The soles of shoes are crushing the fine gravel, and the sleeves of a jacket swoosh with each movement of the arms. I am standing on the grass under a tree, and the man—who walks by only a few meters away—cannot even see me in the dark. He walks slowly, almost languidly. He reaches the ledge of the wall, looks around, and lights a cigarette. He’s waiting for me. The moon hasn’t risen yet tonight, and under the broken lamps I only see a silhouette. The glowing cherry of a cigarette moves from the waist to the mouth, and then back; again, up and then down. He seems calm, looking somewhere into the distance, waiting. I look him over for a minute or two, and only then do I leave my cover.

Prague Noir

Prague Noir